Although much of our attention related to COVID-19 has been focused on how SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted among humans, researchers have been closely monitoring its presence in Canadian wildlife as well.

In late 2021, a research team from Sunnybrook Research Institute and key collaborators detected SARS-CoV-2 infection among deer in Québec. Since then, deer in other provinces have also tested positive. The virus has already been detected in deer in the United States as well, with a study in late 2021 showing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in 40 per cent of blood samples collected from deer in Illinois, Michigan, New York and Pennsylvania. It’s not currently known how the virus was transmitted to deer, although there do not appear to be overt signs of illness in the animals.

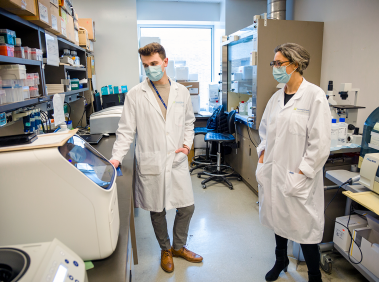

This work is part of a national research collaboration established in 2020 to detect and characterize SARS-CoV-2 activity in wildlife, led by government and academic scientists including Dr. Samira Mubareka, virologist and infectious diseases physician, and post-doctoral fellow Dr. Jonathon Kotwa, both at Sunnybrook, alongside collaborators at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), le Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs (QC), the Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry (ON), University of Guelph, Carlton University and Trent University. In total, the group is analyzing thousands of samples from a variety of wildlife.

Below Dr. Mubareka and Dr. Kotwa discuss the importance of monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife and the implications the recent findings may have on the course of the pandemic.

Why is it important to closely monitor the prevalence of COVID-19 in wildlife?

Dr. Mubareka: The emergence and rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 has sparked concerns of spillover from humans to susceptible wildlife populations, raising the possibility that new wildlife species could ultimately serve as virus reservoirs, allowing the virus to continue to mutate even after humans have reached immunity.

Dr. Jonathon Kotwa (left) and Dr. Samira Mubareka (right) are part of a team detecting and characterizing SARS-CoV-2 activity in wildlife.

Through a collaborative effort between academic and governmental research groups, surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in wildlife is ongoing in Canada and is conducted using a One Health approach. One Health recognizes that human health and the health of other animals are interconnected and emphasizes the importance of a coordinated and collaborative approach to achieve the best outcomes for all species.

What can the discovery of SARS-CoV-2 in Canadian wildlife tell us about the future of the pandemic?

Dr. Kotwa: The results of our surveillance work are helping us understand where to look for the virus in wildlife. We have learned that as the pandemic progresses and new variants emerge, the host range of this virus is broadening and shifting. If the virus finds a host, other than humans, where it can circulate and adapt in a sustained fashion (what’s known as a reservoir), the likelihood of eradicating the virus is unfortunately, quite low. This really emphasizes the importance of continued surveillance of the virus in Canadian wildlife.

The good news is wildlife surveillance will enable us to be proactive about emerging variants when they pop up in wildlife hosts to ensure we characterize them and study potential human and wildlife health implications. This way we can implement necessary public health measures if they pose any risk.

These findings also raise questions around how we interact with and impact the natural world. This virus really highlights how interconnected human and wildlife health are in our shared environment. By taking a One Health approach to our surveillance, we can take a step back and think about the bigger picture since it has direct bearing on the direction this pandemic may take.

What’s the next step in this research?

Dr. Mubareka: Next we plan to characterize the viruses from deer, continue with surveillance in wildlife species, and expand our knowledge of animal host response and immunity. Currently, it appears that deer do not develop disease. However, other mammals such as mink can become sick.

In addition, we do not know whether new variants will infect hosts that initially were not susceptible, potentially causing disease – this has already happened with the Alpha variant, which can now infect species of mice that the ancestral virus did not. We do not know whether new variants such as Omicron may do something similar, or how they will evolve in deer.

All of these efforts will continue to rely on strong collaboration and coordination. We’re fortunate to have a wonderful group of academic, government and community partners working together on this project. Going forward, it will be essential to continue to ensure wildlife surveillance, protection and conservation are integral parts of our public health programs.